Oil Money

Table of Contents

Intro

This project is inspired by an article on oil-backed foreign exchange. Amid the bullish outlook for crude oil, the currency exchange of oil producing countries would also bounce back. Does this statement really hold? Prior to this article by Bloomberg (or many other similar research), market analysts test the correlation between petrocurrency and oil price, instead of the causality. The issue is that correlation does not equal to causality. Correlation could be a coincidence of a math game. We simply cannot draw the conclusion that oil price moves the currency (the cause can be a third common factor such as inflation). Some researchers even introduce bootstrapping which, unfortunately, destroys the autocorrelation of time series. Thus, it is necessary for us to apply empirical analysis and computer simulation on various petrocurrencies to examine the underlying phenomenon.

The following figure is a global oil production choropleth. The map lists out a couple of petrocurrencies with potential arbitrage opportunities. What can be easily overlooked is that some of the oil exporting economies peg domestic currencies to US dollar. For the central banks, the peg eliminates the volatile currency risk for oil exporting. For the traders, the room for petrocurrency arbitrage is squeezed. So it is crucial to verify the exchange rate regime of any oil exporting country from wikipedia before moving onto any further analysis.

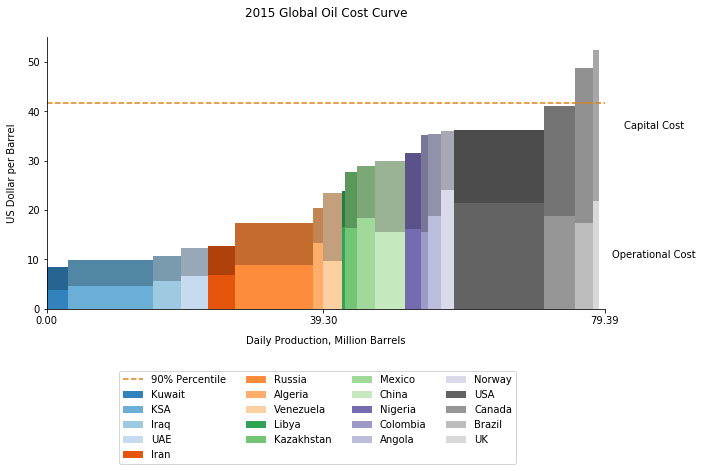

The figure below is a global oil production cost curve. Don't ask me why the data is 2015. They said data is the new oil, this is true especially when it comes to oil data. As we can see, the marginal players in this chart are Brazil and UK. Their production cost has reached 90% percentile among these countries. This explains the decade-long inactivity in North Sea oil field. The only feature of Aberdeen has been Angus beef (proudly made in Scotland) since the time of Margaret Thatcher. And for Brazil, I’d say the production cost absolutely has something to do with the corruption probe in Petrobras. Probably it is why iron ore export makes more money than crude oil in Amazon jungles (Vale is de jure privatized yet Petrobras is state-owned). Hence, we will exclude the largest crude oil producer in LATAM from our oil money project.

Okay, enough about bad jokes. You may ask why I talk so much about commodity market at the beginning. If you think quantitative trading is about solving some complex stochastic process on commodity options, prepare to lose a big chunk of money. You simply cannot quantify geopolitical risk or supply disruption by force majeure. Some basic knowledge of underlying commodity is vital to your trading strategy.

Norwegian Krone and Brent Crude

In the original article by Bloomberg, the first mention is Norwegian Krone. Norway is one of my favorite places in Europe. Unlike Qatar or Saudi Arabia or any other Gulf/OPEC countries, the government doesn't heavily rely on oil or gas for its gross income (even though Equinor formerly Statoil is still a major player in Oslo Stock Exchange). According to wikipedia, over 60% of GDP is contributed by services in contrast to approximately 30% by industry in 2016 (arguably those services could still be oil-based like Dubai). Norway has established the largest sovereign fund in the world to hedge against oil price decline, ever since the discovery of north sea oil fields. Norway has non-petroleum industries such as fishing, maritime, renewable energy, etc. I doubt if oil price is the major driver of the exchange rate of NOK. I look into international trading statistics of Norway. Apparently, most trading partners are inside European Union. Prior to this report, I include Sterling and Euro into the price evaluation model of NOK. To my surprise, Norway actually does a lot of business with US. Hence, the model regressor consists of EUR, GBP, USD and Brent Crude.

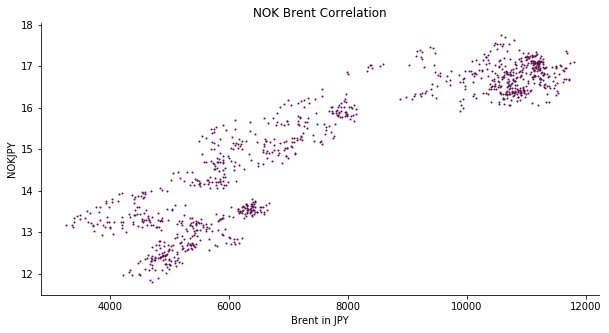

After the selection, we have to choose a base currency to evaluate NOK. It should be a stable entity with free floating FX regime with not much economic tie to Norway. I pick the safe haven currency in East Asia, Japanese Yen. In a released report by OEC, Japan only accounts for less than 2% of exports in 2017 which makes a perfect candidate. Then all regressors in the model would be priced in JPY. Some of you may question why we do not use trade-weighted exchange rate. Indeed, trade-weighted exchange rate is a better choice as it eliminates all other trading partner currencies in the model. The model can solemnly focus on the exporting commodities. However, the pain point is how to construct such exchange rate index. When we talk about trade weights, do we refer to surplus or deficit or total amount of trade? A country can certainly trade with more than 100 partners. Is it reasonable to include every trading partner currency into the weight? Or at what percentile of trade in values do we cut off the list? Why does that percentile make more sense than the others? Constructing a new index is rather state of art than social science. Obviously, it is easier and more efficient to use a non-trading partner currency for evaluation of all the variables. Hence, our regressor variables become EURJPY, GBPJPY, USDJPY and Brent Crude in JPY. Our regressand variable is NOKJPY.

Arguably, the model should involve natural gas (Dutch TTF?) as well. From the website of norskpetroleum, Norway supplies 25% of EU natural gas demand (mainly France and UK). It is interesting that many natural gas contracts are not tied to gas benchmark such as Henry Hub or TTF. In most cases, the price is linked to Brent, sometimes even coal.

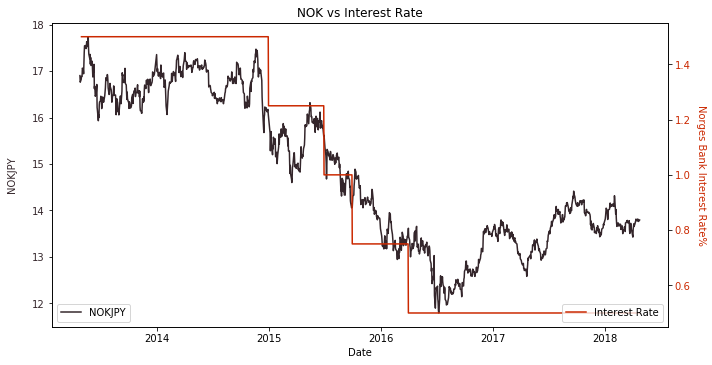

Of course, there are other elements that affect NOK. It is widely acknowledged that change of interest rate impacts the foreign exchange significantly. However, the downside of interest rate is its slow response to the financial market. Central bankers assess the overall condition and review their decisions carefully and patiently. The rate hike may only occur after pickup of inflation rate or employment rate. It could be several times one year and silent for the next couple of years. By the time inflation rate is boosted by soaring oil price, NOK has priced that factor in for a long while.

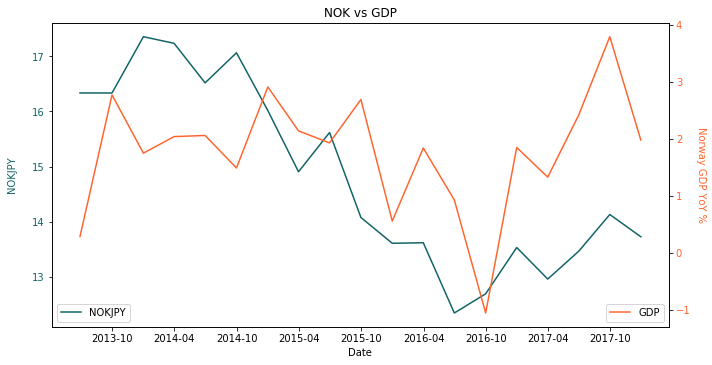

Another important element is economic activity, GDP Year-on-Year growth. Inadequate amount of the data is its biggest flaw. GDP is usually released by statistics bureau quarterly. Forex market is agile and it moves every weekday 24/7. We cannot trade only 4 days a year and stay put for the rest of 246 days. Some indicators are seen as early signs, such as active oil rigs or social financing. These indicators are released on a monthly basis, slightly better than GDP.

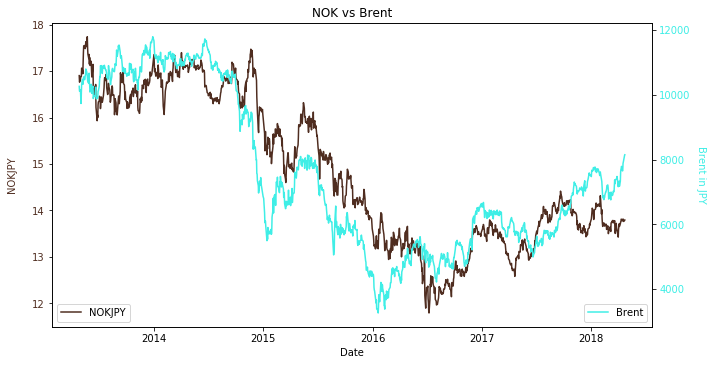

Thus, Brent and other currency pairs are undisputedly better inputs to reflect whether NOK is undervalued or overvalued at the moment.

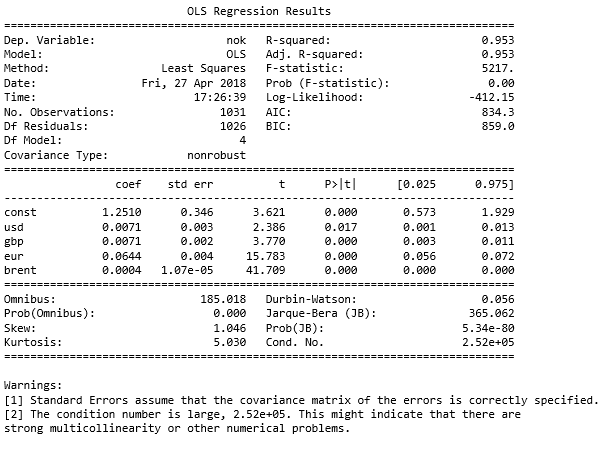

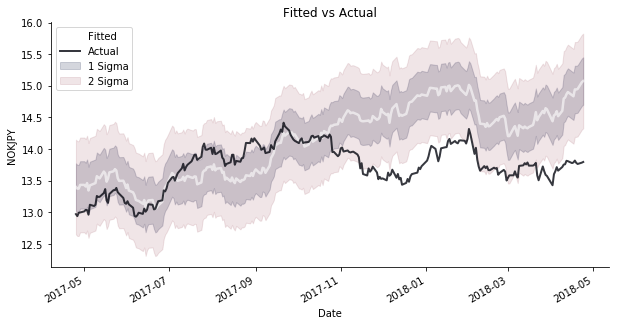

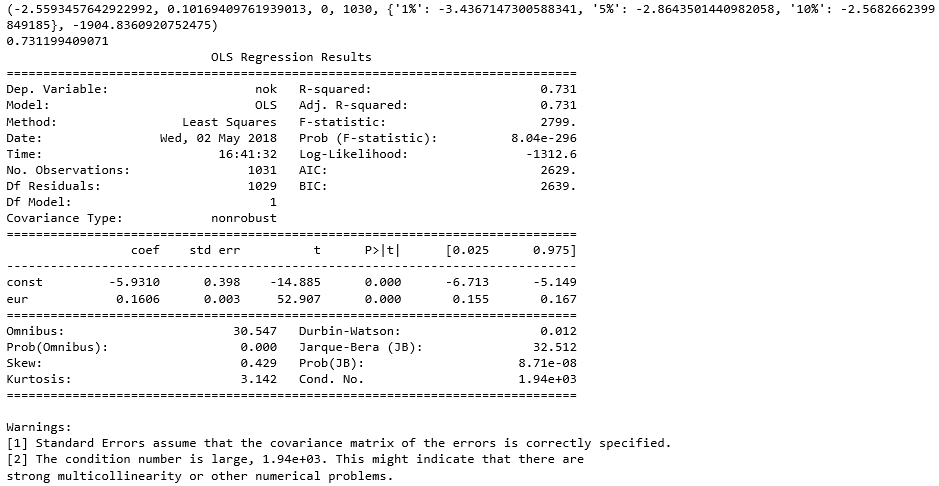

The data of the past five years is collected from Thomson Reuters (now called Refinitiv). We denote the time horizon before 2017-04-25 as training period. We use that period to fit a regression model. From 2017-04-25 to the end of our dataset is defined as testing period. We use our model from training horizon to predict "reasonable" range of the value of NOK in testing horizon. This is a standard practice called cross validation by data scientists. Economists call it out-of-sample data for forward testing and in-sample data for backtesting. The regression result comes out as below. We have a pretty high R squared. All T stats and F stats seem to be significant. I have to take back my words. Brent shows a major influence on NOK which implies Norway still heavily depends on petrochemical industry. As the summary suggests, there could be multicollinearity (condition number is large and R squared is large). Obviously, Brent crude and US dollar should be negatively correlated. Most commodity future contracts are priced in US dollar. When US dollar appreciates or depreciates, the underlying commodity price is likely to go the opposite direction. There could be a cointegration relationship between Sterling and Euro for pre-Brexit time as well.

In this case, we will use elastic net regression to implement regularization. Elastic net is a statistics/machine learning technique that consists of both Lasso (L1) and Ridge (L2) regression to act as a penalty. Ideally it is a perfect tool for multicollinearity issues.

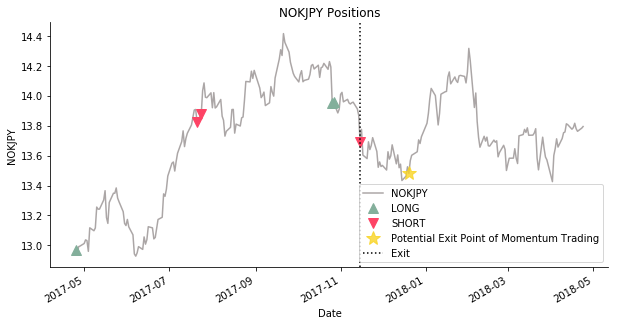

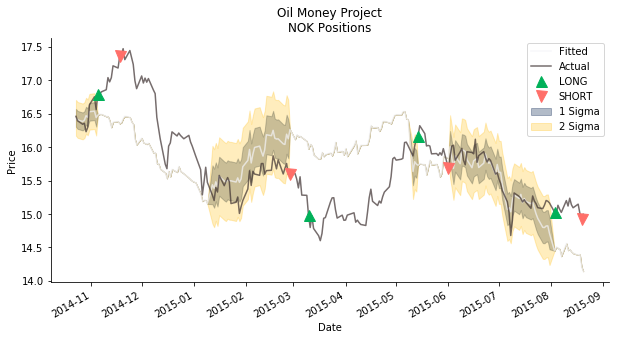

Before backtesting, we ought to set up thresholds for signal generation. One sigma two-sided range is the common practice in statistical arbitrage. When actual NOK price goes above the upper threshold (larger than one sigma), we take a short position. We hold the belief that NOK is overvalued and it should fall back to its normal range very soon. Vice versa. However, the model is based on historical data. No models can precisely predict the future from the past. Our estimation is most likely to be overfitted and fail very quickly in the near future. We need to set up some thresholds for stop orders. When the model breaks, we could clear our positions and exit the trades gracefully. In that case, let's use another golden rule in statistics, two sigmas with 95% confidence interval, to do the trick. If NOK deviates 2 sigmas away from our fitted value, we need to realize the model is broken and we shall exit the trades right away. The figures below show the initial trading strategy. They demonstrate the positions of our statistical arbitrage and the actual price movement against the fitted value within confidence intervals.

To our surprise, there is a strong momentum after our model breaks. The momentum is independent of the selection of our training horizon. In another word, no matter which period we use as training horizon, the strong momentum always follows through right after the model breaks. The failure of this model doesn't really upset me. On the contrary, it is a blessing in disguise. What I see is an opportunity for trend following strategy! We will get back to that very soon.

What also interests me is why the model fails after 2017/11/15. Well, there is no way that a universal model can exist and work forever. Most models have short memory due to the dynamic environment of macroeconomics and geo-politics. Based on adaptive market hypothesis developed by Professor Andrew Lo from MIT, the players in the market are always evolving along with the fast-paced environment. Therefore, we should anticipate our model to lose its power sooner or later. Still, what is the cause of the break? For a quantamental analysis, we have only completed the quant part. I would not get into too much of rigorous and boring part of the fundamentals. Instead, I intend to bring up a short but insightful discussion here. What could possibly be the reason of this dramatic change? Could it be that Saudi and Iran endorsed an extension of oil production cap to boost up the oil price on that particular date? Or Donald Trump got elected as POTUS so he would encourage a weak US dollar and lift up restrictions on oil export as promised during his campaign? If we consider the price of NOK as a stochastic process, we can decompose NOK price into long term trend and short term random disturbance. Well, apparently short term is dominated by Brent Crude. It partially justifies our model. What really drives the long term trend though?

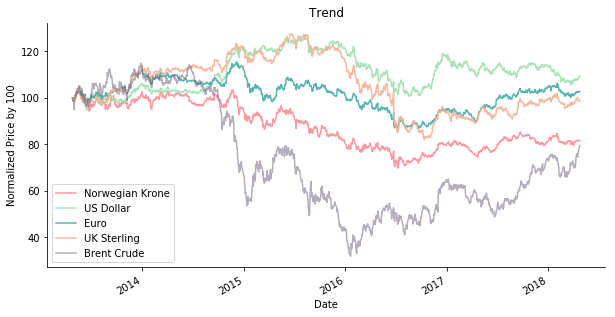

Ta-da, its Euro. As Norway is in EEA, its economic tie with EU totally dominates the long term trend of NOK. From the normalized figure, we clearly see the trend of both NOK and EUR are somewhat correlated. To get a formal conclusion, we need a cointegration test. Nevertheless, there is no Johansen Test in statsmodel package (not on the date when the first draft of oil money was finished, but there is now). We would have to use Engle-Granger two step test. I have to honorably mention that this method is co-developed by the mentor of my mentor, Robert F. Engle, a Nobel Laureate! Unfortunately, we can't get any confirmation of cointegration from the test. The residual of the first step regression is not stationary under Augmented Dickey-Fuller Test. Sometimes we have to use the old fashion way to make a qualitative judgement, rule of thumb. Most researchers in big organizations recalibrate their forecast with policy or experience or consensus views or simply instinct (as an insider, I guarantee you this is 100% true). This is the moment that I exercise my sacred right to declare that EUR is the driver of NOK's long term trend!

Well, I am not an economist (even though my work has a lot to do with them). I do not expect to really find out what happened on 2017/11/15 through our quantamental analysis. Let's call it an end to this twist (if you are an economics-savvy person who is eager to know more, feel free to read this paper by the Central Bank of Norway). In fact, we can simplify our model to NOK driven by Brent. From an econometrician's perspective, it does not sound like a good idea. Every coefficient of the model is statistically significant. Adding more variables does not worsen AIC, BIC or adjusted R squared. There is no incentive for us to remove variables as more information in the model is always better. From a trader's perspective, the requirement is a universal model. Ideally, the model contains two variables, one is the underlying petrocurrency, the other is the local crude oil contract. In this sense, the reduced form model can be replicated to any petrocurrency without too much focus on analyzing trade partners or exporting products. The argument here could be, is linear regression model too naïve? Nick Patterson, a cold war cryptographer who later worked in Renaissance Technologies, said (check here for the original version of 45-minute-long interview),

One tool that Renaissance uses is simple regression with one target and one independent.

It’s simple, but effective if you know how to avoid mistakes just waiting to be made.

In the world of modelling, the identification is far more important than the estimation. As long as we find an element with causal effect, there is no need for fancy spatial time series analysis when we can solve everything in its simplest form. We will take the trader's perspective in the following context.

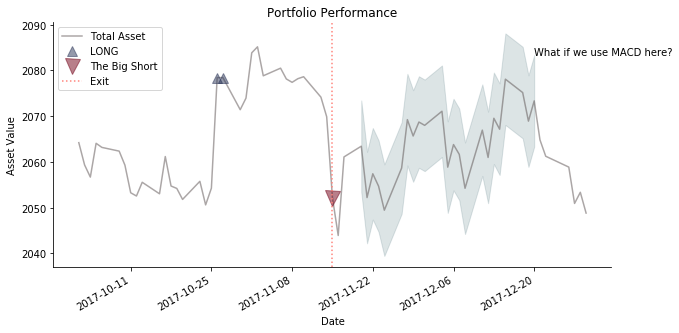

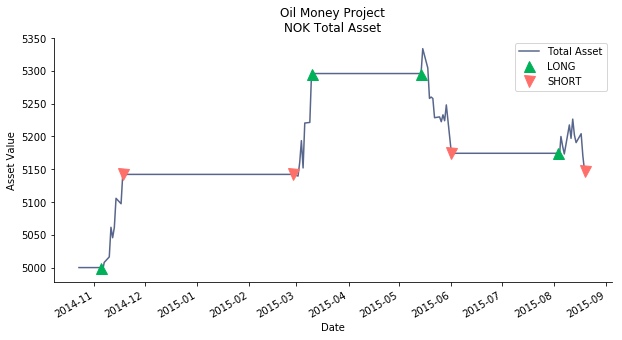

Next, let's take a look at the portfolio performance. So far so good, we actually make a few bucks from statistical arbitrage. Interestingly, after we place the stop order, I decide to add an extra position to see what would happen if we follow the trend. In the figure below, we could see the downwards momentum doesn't stop until two months later (probably another major event in financial market).

Wow, did we just discover a momentum trading strategy! We started off this project to seek for a statistical arbitrage opportunity between crude price and petrocurrency. What we got in the end is an entry signal of momentum trading strategy. Also, we found out Euro is the major and long term influence on Norwegian Krone, and Brent Crude is the short term disturbance. My explanation for our discovery is that, when the model breaks, there must be something fundamental that change investors' outlook in NOK or Brent, e.g. an increase in north sea refinery capacity limit. That sort of change is supposed to last for quite a while which offers us a chance for trend following (this is how CTA makes money).

Here are the rules of our latest momentum trading strategy.

- The first step is always about regression. Run linear regression on NOKJPY and Brent in JPY of the past 50 data points. If the R squared exceeds 70%, the model is deemed as valid, which has successfully verified the petrocurrency status of Norwegian Krone for the past 50 trading days. Then the forecast derived from the model becomes reliable.

- Calculate the standard deviation of the residual. Set +/- two sigma from the predicted price as the threshold to trigger trading signals. If the actual price sits above the upper threshold, the position is net long. If the actual price sits below the lower threshold, the position is net short.

- Once the trade is executed, a counter will start as well. It will keep track of how long the position has been held. If the holding period exceeds 10 days, the position will be cleared. Because the underlying momentum could have vanished into the thin air after such a long time.

- Meanwhile, if the absolute spread between the current price and the entry price exceeds preset limit, which is 0.5 points by default, the position will be cleared to claim profit/loss. The preset spread limit varies along with each individual's risk averse level. When the market gets too volatile, it is sensible to reduce the risk exposure.

- After the position gets cleared, the model has to be recalibrated by the latest 50 data points. Now that a trade cycle has completed, the whole thing goes back to the first step. So on and so forth.

As shown in the portfolio performance, each momentum takes different length of time to decay. Holding the position too short may not reach the peak of the asset price. On the other hand, Holding the position too long may surpass the peak and head towards the lower side of the profit curve.

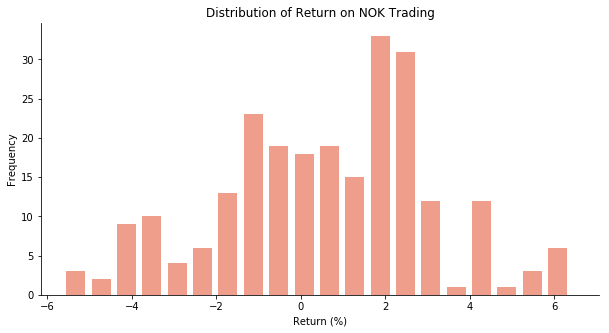

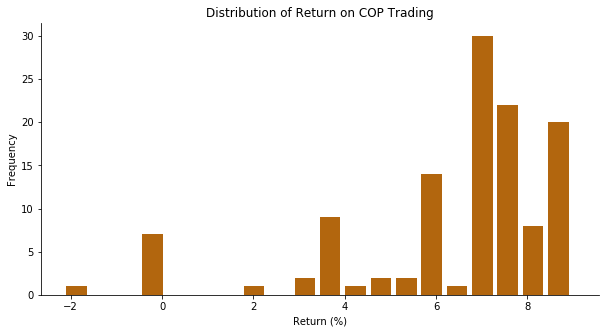

Nonetheless, we are not satisfied with the return. We are greedy creatures. 2% return? Why don’t we deposit the money into the current account and get some risk free interest (Norges Bank interest rate at 1% as on the 30th of April, 2019)? We certainly need to tune the parameters, such as different holding period and stop loss/profit point (even the amount of backtesting data points or acceptable R squared level), to maximize the return. After several attempts, we have gathered the below statistics. In average, the return is around 2%, positively skewed. Yet, extreme values can go as far as -6% to 6%. Needless to say, 6% is the goal.

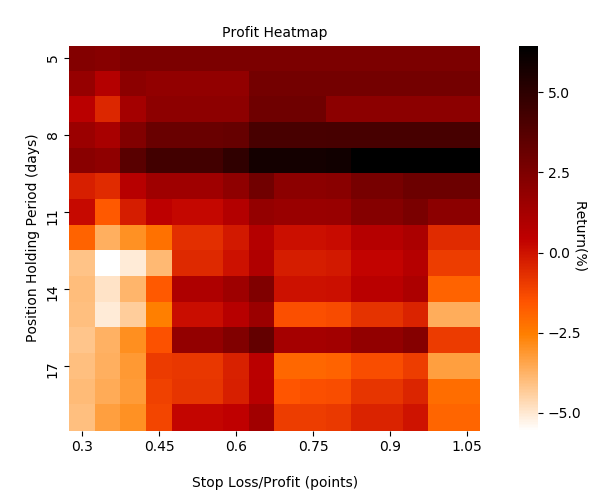

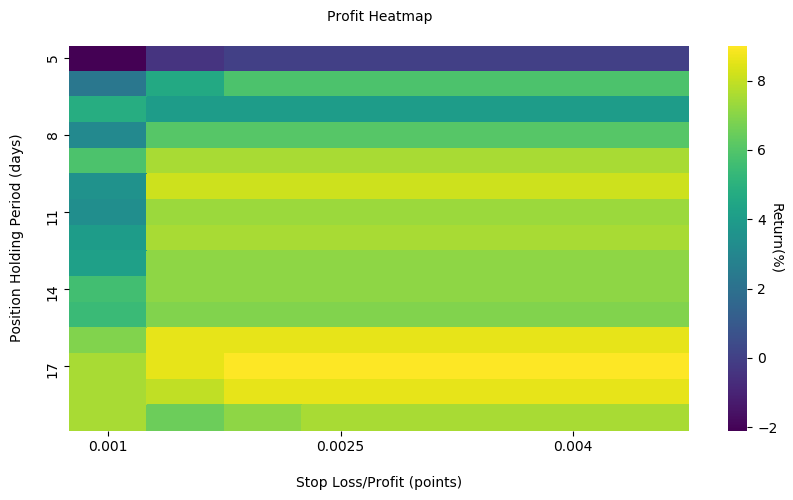

The heatmap below is the visualization of return using different parameters. The darker the tile is, the more money you make. From the chart, you can easily tell stop profit/loss point doesn’t have much explanatory power on the return. The return is more correlated with the length of holding period. It makes sense since this is a trend following strategy. The optimal holding period to maximize the return appears to be 9 trading days. The optimal stop loss/profit point is more flexible, which could range from 0.6 to 1.05.

It turns out that our momentum trading is much more robust and profitable than our original idea of statistical arbitrage. But does it work on any other petrocurrencies? Unfortunately, Norway is one of the largest oil producing countries with floating FX regime. The rest are US, Russia and Canada. US dollar is a totally different case. Petroleum business only takes up a very small share in US economy even including shale boom in Permian Basin. What about Russian Ruble? Well, let's find out!

Russian Ruble and Urals Crude

For Norway, I may have doubts in how much petroleum business contributes to its overall GDP. As for Russia, I suspect if any person in her/his rightful mind would question the role of oil in the economy of Russia. According to Wikipedia, Russian oil business (mostly Rosneft) accounted for 16% of GDP, 52% of federal budget revenues and over 70% of total exports in 2012. Usually, countries with large natural resource reserves suffer from Dutch Disease (USA is an exception), especially Russia! Hence, we don't need any extra step to validate if Russian Ruble is a petrocurrency.

First step, let's identify the regressors. If we look at trade statistics, the biggest trading partners with Russia are EU, China, Ukraine, Belarus, Japan and Korea. Belarusian Ruble BYR is very strange. It has been pegged to both Russian Ruble and US dollar. But the central bank interferes the currency rate too frequently. I would argue the currency regime is a completely mess (thanks to oligarchs). I'd rather not include Belarusian Ruble as it is not a big player in global or regional economy. So we are left with Euro, Chinese Yuan, Ukrainian Hryvnia, Japanese Yen and Korean Won.

Australia, another country with rich natural resources, basically doesn't make many direct trades with Russia. Fantastic! Australian dollar can be leveraged as the base to evaluate RUB,EUR,CNY,UAH,JPY and KRW. Instead of Brent, Russia has its own version of blending called Urals. We would take Urals spot price as a benchmark for oil. Apart from Urals, Russia also exports natural gas to Europe via Gazprom. The best benchmark for natural gas in the continent is Dutch TTF gas future contracts. When the tension of Nord Stream 2 pipeline is settled, the benchmark is probably gonna be German NCG gas future contracts (or maybe some extra benchmarks for South Stream and Power of Siberia). The saying goes, gas is the power and oil is the money when it comes to Russian exports. There we go, the preparation is done.

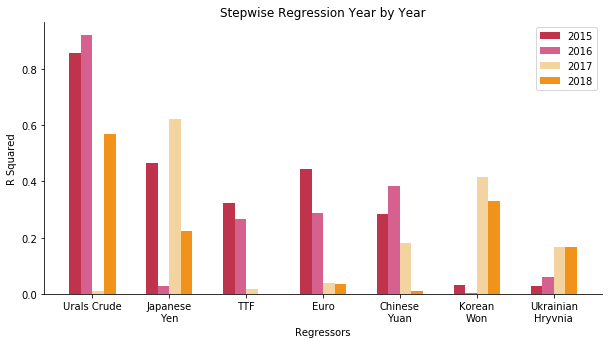

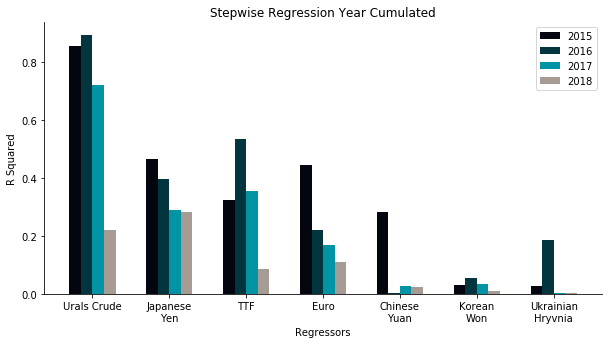

Yet, Russian Ruble is very special. Russia has been sanctioned by US and EU for so many times (really feel sorry for those innocent Russian civilians). To know when and what, someone actually creates a timeline for us. Each major sanction should make a huge impact on the currency. In this case, we use a method called stepwise regression to test each potential regressor for each year. We would pick out the R squared winners out of 7 variables from the past 4 years to construct a robust model. The figure below shows R squared of each variable for each year.

The figure below shows R squared of each variable for cumulated years.

Here are some interesting facts. Apart from Japanese Yen, Korean Won and Ukrainian Hryvnia, R squared year by year on other currencies or commodities are literally plunging from 2015 to 2018. The biggest cause is the sanctions. Ever since the annexation of Crimea, military intervention in Syria and nerve agent attack in UK, the sanction on Russia is getting more and more severe. Most countries except some rogue ones (e.g. China, Iran, Venezuela) decline to trade with Russia. Thus, we are able to observe the R squared downhill of Dutch TTF gas, Euro and Chinese Yuan over the years. Even though R squared on Urals jumps up in 2018, there is another key indicator that warns us of the danger. We would find out very soon. Before that, it is also strange that there are some spikes of R squared on Japanese Yen. My initial guess was that Japanese Yen became the safe haven for Russia turmoil. Frankly, it is more of a coincidence after some digging into the data. The spikes are simply because of the sluggish growth of Japan economy, which coincides with the downtrend of Russian Ruble. The same applies to Korean Won. As for Ukrainian Hryvnia, its R squared barely exceeds 20% so we simply ignore it. Now let us take a look at R squared of year cumulated. We could easily draw the same conclusion as before that R squared of most regressors are declining over the years (Korean Won looks like a bell shape curve though). 2017 and 2018 seem to be the roughest years for Russia. In that case, I prefer to split the backtesting data into pre-2017 and post-2017.

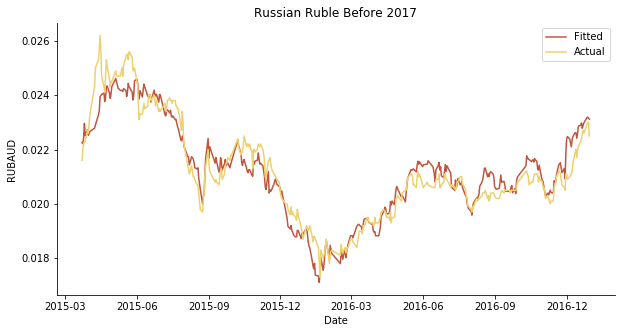

For pre-2017 data, the model seems to be very robust. Urals alone explains more than 80% of the price movement of Russian Ruble. The introduction of Euros into the model is optional. It indeed increases a significant amount (more than 2%) of R squared compared to other regressors. AIC, BIC and adjusted R squared also justifies the theory. Although in the following models, we would only include Urals Crude as a regressor. The reason behind that is to keep the model consistent across different currencies and different commodities (recalled from NOK section, we prefer trader's perspective).

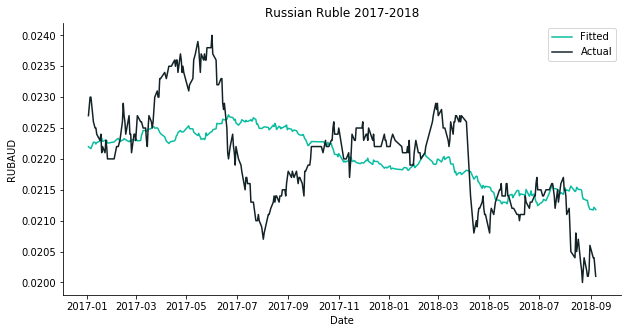

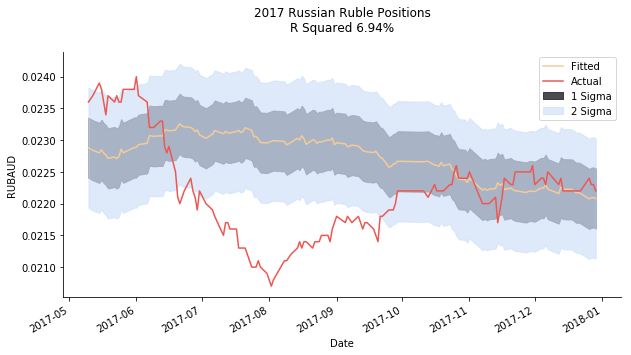

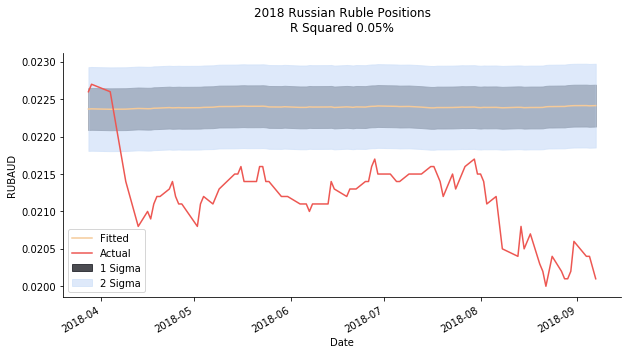

For post-2017 data, we can tell this is when the sanction bites. Urals can only explain less than 30% of the price movement of Russian Ruble. Moreover, the coefficient of Urals is even negative which contradicts the fact that Russian Ruble is a petrocurrency.

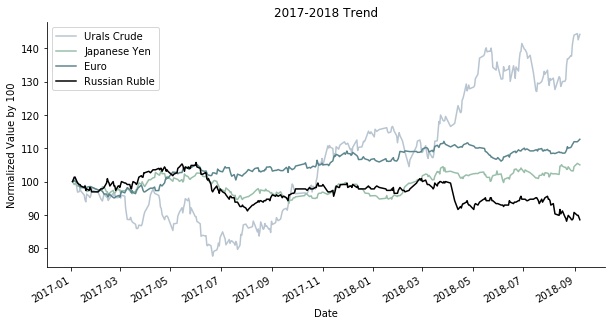

If we track the price for Urals, Japanese Yen, Euro and Russian Ruble from 2017 and 2018, we will get a clear picture of how these assets move along the time axis. The stagnant performance of Japanese Yen and Euro implies the post-recession economy growth of two of the most influential blocs in the world. The surge of Urals from the beginning of 2018 does not translate into the performance of Russian Ruble. The sanction on Rusal which deeply disrupted aluminum market and the sanction in response to Russia’s gas attack on UK soil hit Russian Ruble further down.

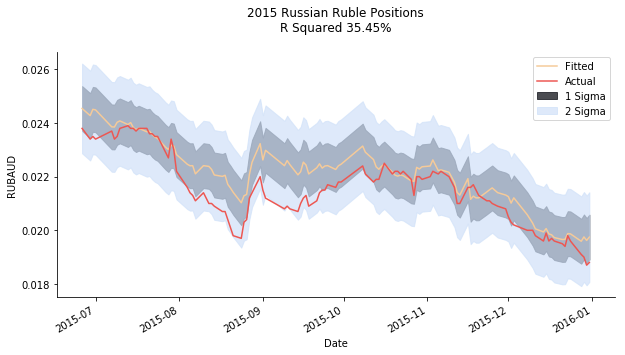

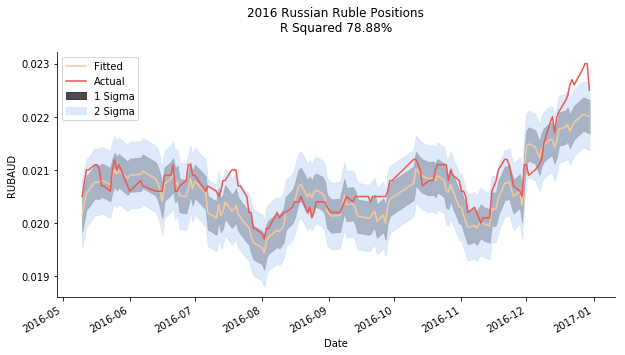

In terms of trading strategies, Russian Ruble is too geopolitical event driven for any quantitative analysis. What we do here is trying to split the data of each year with a ratio of 30:70 into training and testing. We would apply whatever we have learned from the training dataset to backtest our momentum trading entry points. For the first two years, our model captures pretty solid R squared. The actual price of Russian Ruble barely drifts two standard deviations away from our forecast price. Nonetheless, there are two sides of this story. The good news is that our model identification is perfectly correct but the bad news is that our strategy only works when the model begins to break. We only want the model to be 80% correct instead of 100%! As an old saying goes, there is no way to beat the markets if the markets are fully efficient.

For 2017 and 2018, the R squared becomes total failures. It drops from less than 10% to less than 1% within 2 years. Still, you can argue that this strategy sort of works. When the model breaks in 2017, the downward pressure on Russian Ruble lasts more than a month. Although it sounds very tempting for the wide margin we can exploit, the R squared for that model is only 7%! Is it really worth the risk? I don't know what you folks think. I had a formal academic statistics training. A model with ridiculously low R squared and insignificant coefficients does not appeal to me. I strongly urge people to be cautious. When the model isn't robust (say R squared less than 50%), this trading strategy isn't plausible.

My conclusion for Russian Ruble is DON'T TRADE IT!! Its political agendas always screw up its petrocurrency status. A recent article by Financial Times coincides with my theory. Trading is more like a marathon rather than a 100m sprint. Nobody would love to see sanctions kick in like Bête Noire. I don't really think Russian Ruble is worth the risk. Is that it? Nope, lucky for us, we still have one more petrocurrency, Canadian Dollar, to test our strategies.

Canadian Dollar and Western Canadian Select

For some bizarre reason, everybody says Canadian Dollar is a petrocurrency. We all know Canada is a country with huge deposits of natural resources. However, it never strikes me as a heavy weight player in the petroleum industry. According to Canadian government, Canada is the fourth largest crude oil exporter. But hey, why does it catch so little attention in the oil market? Because 96% of its production is shipped to Uncle Sam. Similar to U.S., Canada has oil pipeline bottleneck as well. Both have attempted to expand the capacity. But both have faced huge resistance from indigenous people and environmental protection.

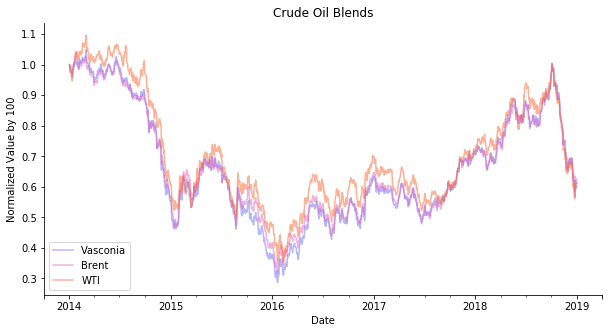

For Canada, there are two major local crude oil contracts we need to take into consideration. One is Western Canadian Select. In contrast to the conventional crude oil, WCS comes from oil sands. It is extracted via open pit mining or steam injection rather than oil rig drilling. The molecular level of WCS is quite heavy and its sulfur content is graded as sour. The other local contract is called Edmonton Synthetic Crude. It is a form of light sweet crude oil upgraded from oil sands. The upgrade facilities break down the heavy molecule and remove sulfur content from bitumen. Thus, the synthetic crude can directly flow to refinery as inputs. Because the crude oil export mainly serves the Yankees, we choose West Texas Intermediate, the domestic benchmark for U.S., instead of Brent. You can check Alberta government website for the pricing of WCS.

Based upon the information from International Trade Centre, mineral fuel is not the only export. Canada also exports a lot of other natural resources including natural gas, precious gems, base metals and agricultural products. In that sense, we also welcome gold and LNG into the model.

Despite both Canada and Australia are in Five Eyes Alliance, the trade flow between Canada and Australia is quite limited. Australian dollar becomes the ideal base currency. Canada is a member of NAFTA. It is no surprise that both United States and Mexico are Canada’s predominant trading partners. Also, Canada is in the ring of Asia Pacific. It maintains active trading relationships with west Pacific countries like Japan, China and Korea. The only surprise is the trade flow between Canada and EU (including UK). Hence, we come up with a model contains WCS, Edmonton, WTI, LNG, Gold, USD, MXN, EUR, GBP, JPY, CNY and KRW.

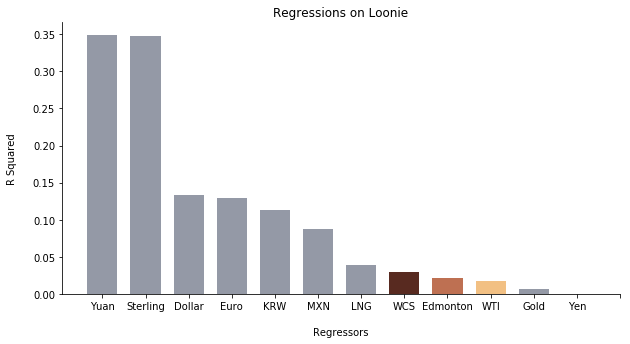

When we run regressand on each regressor individually, in-sample data regression shows no sign of petrocurrency at all. None of the hydrocarbon products (as highlighted in the figure below) have R squared over 5%! The astonishing result really contradicts the market belief that Loonie is a petrocurrency.

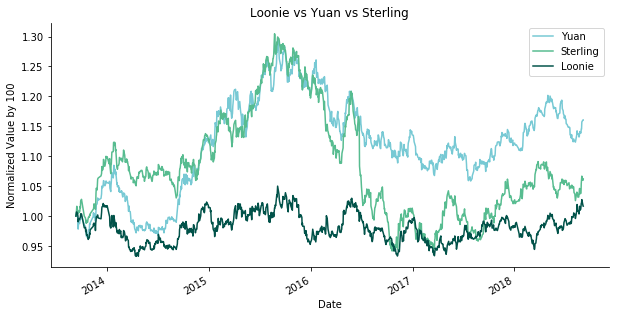

Nobody has expected 35% of the outcome can be explained by UK Sterling and Chinese Yuan. It is quite unusual that US dollar does not have the strongest R squared. If we look at GBP and CNY, normalized values on forex imply UK Sterling and Chinese Yuan were in sync until Brexit referendum ruined everything. The cointegration between GBP and CNY doesn’t make a lot of sense. Is it because of the golden era between UK and China?

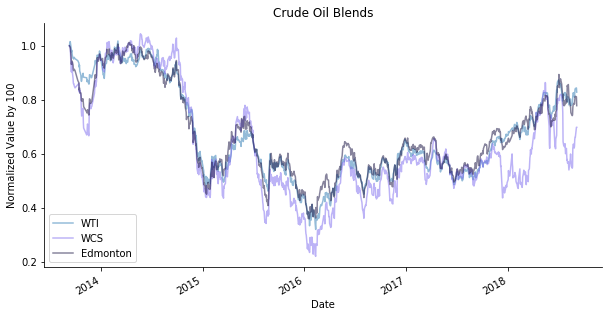

If we look at the hydrocarbon products, normalized values on crude oil blends demonstrate that Canadian blends are indeed associated with West Texas Intermediate. The light sweet synthetic crude is closely stick to the movement of WTI. WCS drifts off the course occasionally. It is probably caused by some tightening market condition (e.g. the reduction of heavy sour refinery capacity by force majeure). In general, all three crude oil contracts move towards the same direction. With that being said, we can exclude the possibility of faulty petroleum data. So where does the theory of Canadian petrocurrency come from?

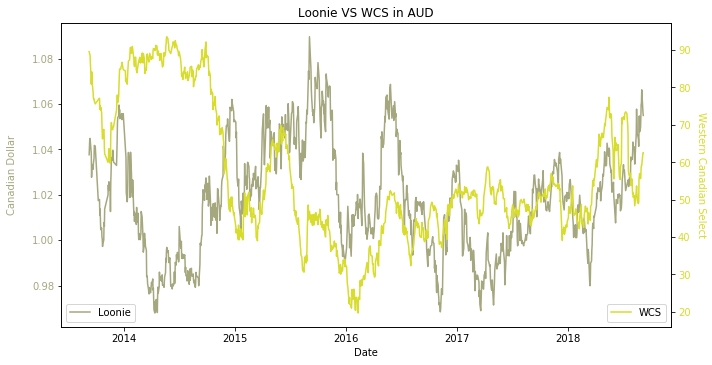

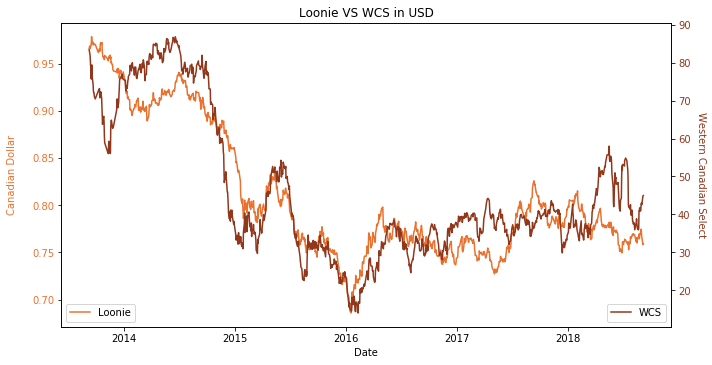

Let’s take a step back and look at what most market analysts focus on. Most studies on Loonie use raw exchange rate of CADUSD. As shown by the figures below, Loonie and WCS priced in different currencies show diverging results. It appears that so-called petrocurrency status is possibly due to the dollar effect. Most commodities are evaluated in US dollar. It’s very intuitive that the commodity price in US dollar tends to show a smaller volatility compared to the commodity price in other currencies. The reason is quite simple. For commodities priced in other currencies, they need to convert to US dollar for international settlement. US dollar is the one and only global currency (hopefully Euro can find its rightful place). Given the bid and ask spread of currency exchange, it tends to widen the gap between currency and underlying asset. Some studies use trade-weighted exchange rate. Nevertheless, the bilateral trade between Canada and U.S. makes up 75% of the trade surplus for Canada. The significant impact of dollar effect on trade-weighted exchange rate makes it de facto CADUSD.

Our finding is still not solid enough. Recall how Russian Ruble gets flagged by aggressive espionage? Perhaps Canadian Dollar shows different attributes across different time horizon as well. It is definitely not caused by sanction. It could be the monetary policy change by central bank or one of the revolutionary reforms by Justin Trudeau (no sarcasm intended). To confess, Canada is not the spotlight of the financial market, so most people are not familiar with its internal situation. Thanks to the over publicity of machine learning, we have the luxury to borrow some tools from unsupervised learning.

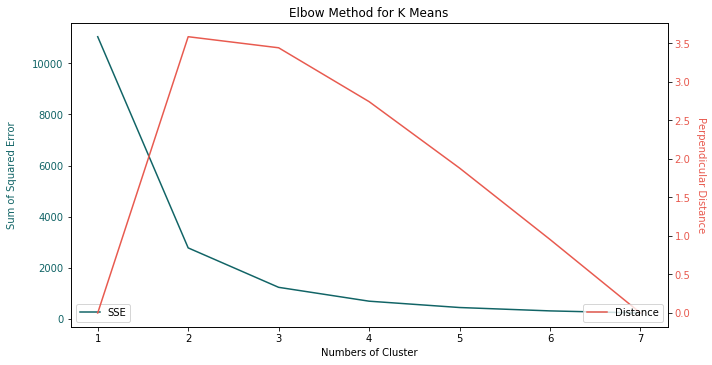

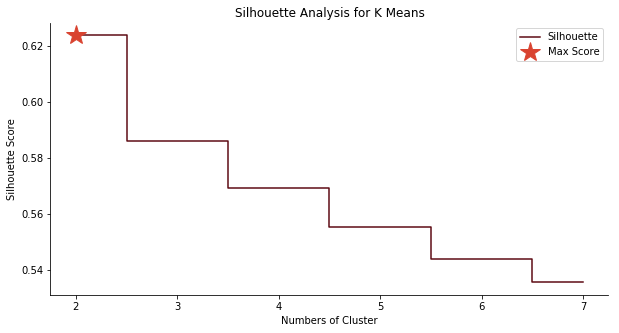

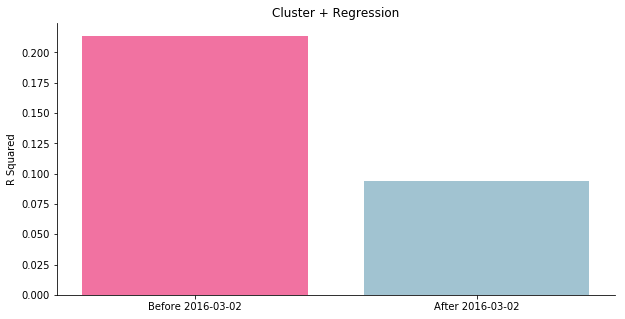

K-Means is applied here to find out the clustering on time horizon. Loonie, WCS and date are the dimensions. There are various techniques to determine the optimal number of the cluster. For this mission, both elbow method and silhouette score are taken into consideration. I have encountered several occasions that two metrics give out two different answers. That is why we ought to use different methods to reach a final decision. Fortunately, we can observe the consistent performance of K-Means with K equals to 2. Thus, we shall split the dataset into two different parts.

There are some shortcomings of using K-Means. While most cluster problems in machine learning focus on discrete variable, the autocorrelation of time series is not taken into account. Hence, we need to visualize the data to make a judgmental call. In some cases, cluster A is uniformly distributed across the time horizon. we do not see a clear threshold on a specific date to separate two different clusters. Lucky for us, we get a clean cut on March 2nd of 2016. The boundary of two clusters is a flat surface on z axis.

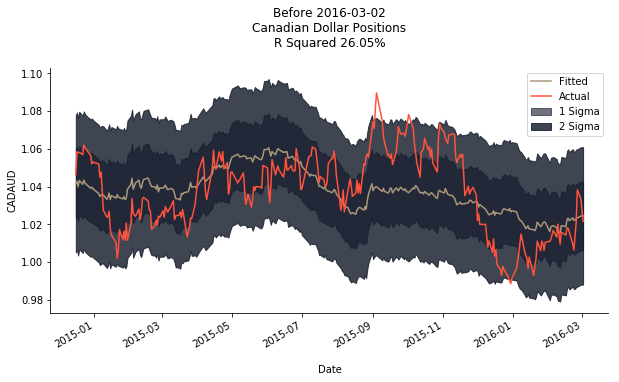

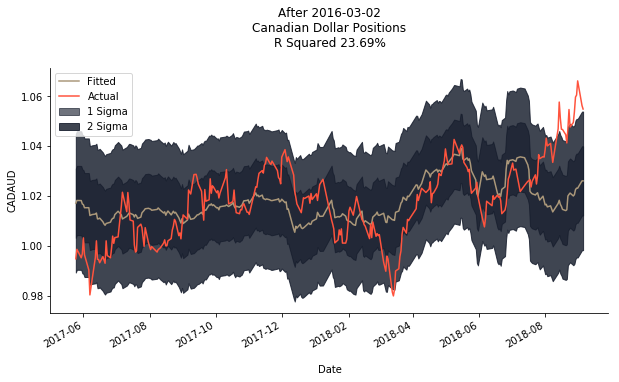

Don’t ask me what happened on March 2nd of 2016. I did a thorough search in the historical archives but came back empty handed. Nonetheless, even if we split the timeframe in regard to the threshold, we still cannot observe a significant R squared from in-sample regression. For the first period, we get respectively 20% R squared. And for the second, we get roughly 10% R squared. It seems that I cannot justify the causal relationship between Loonie and WCS. Is Canadian Dollar really a petrocurrency?

The next step is to conduct out-of-sample regression. The result surprisingly outperforms in-sample regression. For each period, we take a 70/30 train test split. The R squared is guaranteed to be above 20%. Though it hasn’t hit our 70% target. If we merely take a look at the visualization, we will see the actual price is often within the two standard deviation bandwidth.

In a nutshell, we have exhausted approaches to validate the petrocurrency status of Canadian Dollar. I personally do not believe Loonie is a petrocurrency. In 2018, mineral fuel takes up about 22% of the total export, compared to 53% for Russia and 62% for Norway. Loonie and WCS are in sync if and only if both assets are denominated in US dollar. Therefore, I reject the null hypothesis that Canadian Dollar is a petrocurrency. Some market analysts talk about the relationship between Mexican Peso and Maya crude oil. In 2018, the vehicles occupy 26% of the total export. On the contrary, mineral oil is such a niche segment in the export business. The number is as pathetic as 7%. I really hope those analysts can give me a more convincing narrative.

Even though Loonie is not a petrocurrency, that shouldn’t stop us from deploying our trading strategy. Unlike the eccentric volatility of Russian Ruble, the political environment of Canada is harmonic, so unusual spikes are not expected. The model per se is based upon rolling period of the past 50 trading days. The market is dynamic so there will always be a moment when both Loonie and WCS enter Nirvana. The bottom line is the preset model threshold. As long as we can obtain a 70% R squared, the game is on.

Colombian Peso and Vasconia Crude

Thus far, we have tested three different currencies yet only one of them is really applicable. Don't worry, here comes the bonus stage. Just when I thought this project is finished, one day my colleague came to my desk and asked me, "do you know what the biggest export of Colombia is?"

"La cocaína!" I answered without hesitation.

"Well, you watched too much Narcos and Escobar, not that." One of his eyebrows lifted.

"Prostitutes? A large part of web cam models come from Colombia, maybe de facto Venezuelan refugees in Bogotá or Medellín."

"Jeez, if I am Colombian, I'm gonna execute you the drug cartel way. On the book, it's CRUDE OIL!!"

Lo siento, no offense, Colombians. Surprisingly, mineral fuels took up 52.5% of export in terms of value! In 2018, U.S., China and Panama have taken roughly 76.4% of Colombia's crude oil export. However, it only has a very small market share (not even top 20) compared to other big major oil producers and it is not a member of OPEC. Its supply has been eroded by frequent attacks from guerillas on pipelines from Cupiagua to Coveñas. That's why the country is almost invisible when we discuss the oil market. The good news is we don't really care about how Colombia impacts the overall oil market. We merely want to profit from its currency fluctuation caused by oil export.

Anyhow, let's take a peep at local crude blends in Colombia. The major products are Cusiana, Caño Limón, Vasconia, Puerto Bahía and Castilla (API from light to heavy, sulfur content from sweet to sour). Although Castilla is the major export to U.S. (find more details from EIA), we can only obtain Vasconia price from Bloomberg, so we have to cope with constrained data availability. Similar to Canada, the biggest customer of Colombian crude blends is Uncle Sam. Thus, West Texas Intermediate is a more appropriate benchmark than Brent.

Besides crude oil, Colombia has other exports, one of the most well-known is coffee beans. Colombia is the second largest coffee bean producer trailing only after Brazil. There are two types of coffee beans, Arabica and Robusta. Arabica is the predominant species in Colombia with its bright acidity, sweet notes, and caramel aroma rising from every brew. However, Robusta has a higher yield and less demanding conditions to grow. Concerning the rising menace of climate change, the bitter and intensive taste has been gradually introduced to Colombia as well. Hence, we would love to test ICE Arabica and Robusta futures price to make sure Vasconia crude is the major factor of Colombian Peso. Apart from the high-profile coffee beans, coal briquette is another big export business in Colombia. Most coals are shipped to Europe, so we pick Rotterdam API 2 coal futures as our benchmark. As for the gold in Colombia, we still follow gold LBMA price in London.

If you recall, we have been using Australian dollar to evaluate Russian Ruble and Canadian Dollar. It is still applicable to Colombian Peso. It seems that there are few trades among big commodity exporters. The input of the model also considers Colombia's top trading partners. Inevitably, we have US dollar and Chinese Yuan, the high-tech manufacturer and the cheap-shit manufacturer. It's hard to imagine there is a country in the world who doesn't trade with this pair (even with sanction you can still trade with one of the pair, you know which one). Most of Colombia's trading partners are in Latin America. These trading partners either use US dollar (Ecuador) or issue their own currencies pegged to US dollar (Eastern Caribbean Dollar). All we need is to add a few currencies from south American countries, Argentina Peso, Peruvian Sol and Brazilian Real. Additionally, we cannot forget Mexican Peso and Turkish Lira. You may wonder, what about Euros? What a sad story! US dollar is the one and only global currency. ICE Rotterdam API 2 coal futures are priced in US dollar.

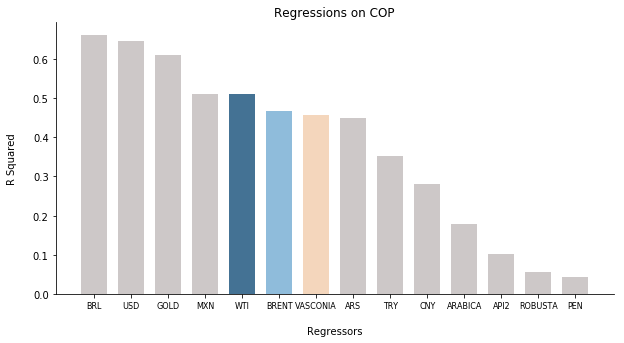

The regression on the input has verified our theory, Colombian Peso is a petrocurrency! Crude oil can achieve roughly 50% of R squared. Coffee beans or coal briquettes do not have R squared over 20%. Although Colombia has a larger market share in these two commodities than oil, they do not have enough influence in absolute USD value.

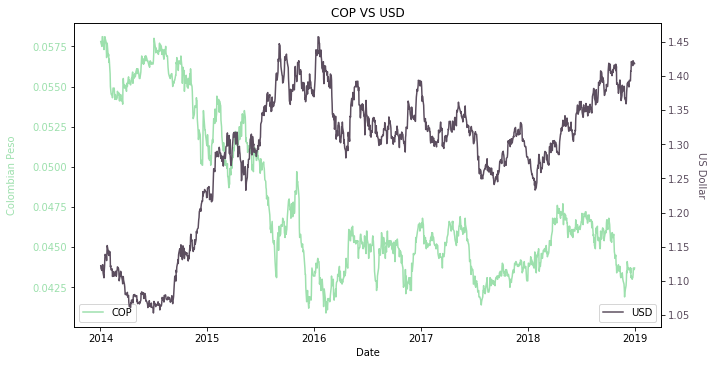

The shining performance of US dollar should be within our expectation. After all, all crude oils are priced in US dollar. Oil price and US dollar are negatively correlated.

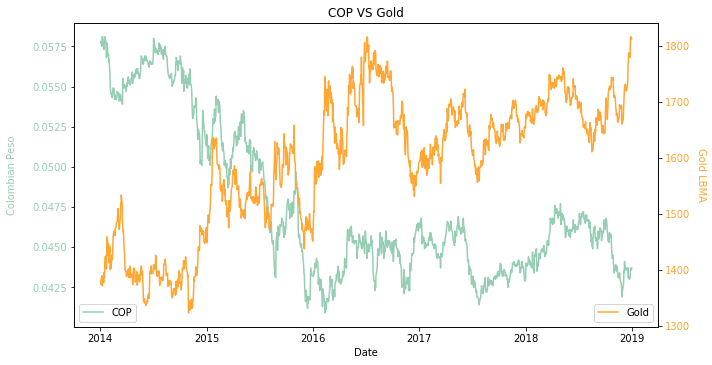

The gold has outperformed crude oil in terms of R squared but its coefficient is negative which implies the gold just represents the negative correlation with crude oil. This is hardly a surprise. Both gold and US dollar are regarded as safe haven assets where crude oil is a leading indicator of the economy.

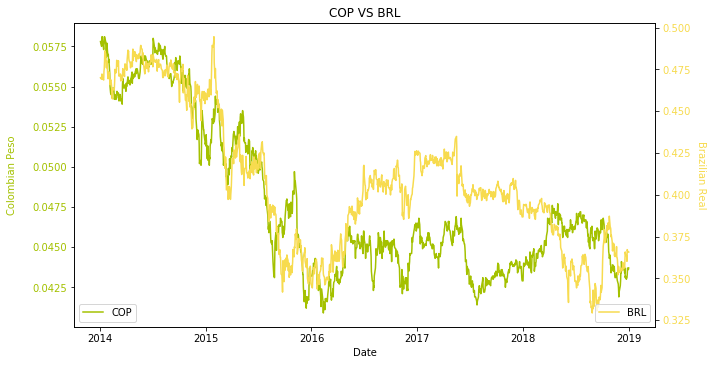

For Brazilian Real, the raison d'être of high R squared is straight forward. Brazil is a huge commodity exporter as well. Brazil and Colombia have a vast overlap in terms of commodity export (you can check OEC for detailed export breakdown). They both export a massive amount of oil, coffee, sugar and gold. Commodity price has a negative relationship with US dollar and a positive relationship with local currency. Thus, we see a quasi-causality between Brazilian Real and Colombian Peso. Why quasi? Colombia doesn't even make it to top 10 of Brazil's trading partners. Brazil has the 7th largest trading deficit with Colombia.

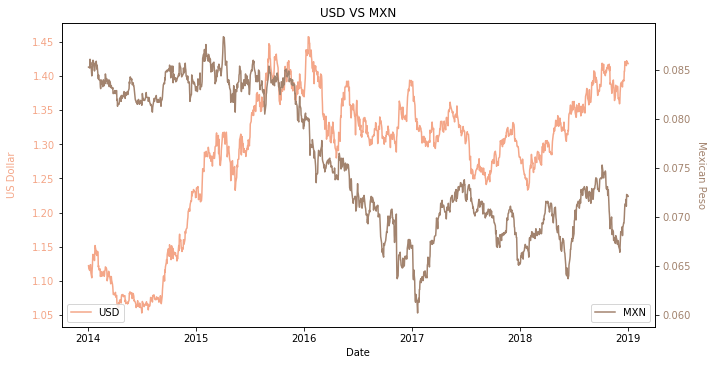

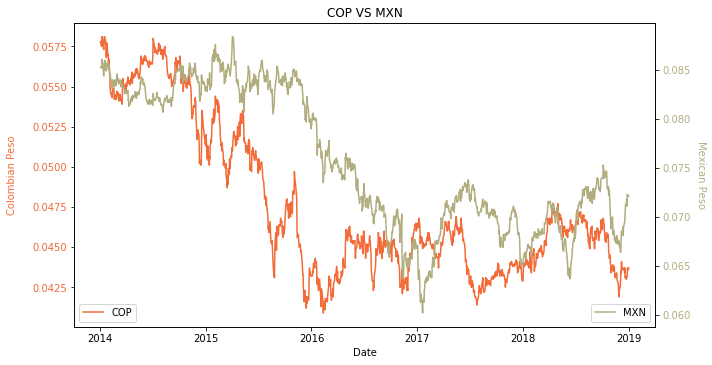

For Mexican Peso, it is slightly complicated. Both Mexico and Colombia have some degree of overlap in terms of commodity export (check OEC for detailed export breakdown). Oil is one of them. Mexican Peso has been called "la petrocurrency" by many analysts. Indeed, we have barely heard of Ecopetrol in Colombia but certainly Pemex with its Maya crude oil. Still, I believe its petrocurrency status was in 2000s. In 2019, the petroleum industry only occupied 5.6% of export. Even in absolute USD value, Colombia exceeds Mexico in oil export. These days the major export for Mexico is automobiles and machineries which Donald Trump has tried very hard to lure U.S. companies to bring back the supply chain. Some other commodities include gold and agricultural products. Yet, it is not a solid argument. Unlike Brazilian Real, Mexican Peso doesn't strictly follow negative correlation with US dollar. They are more like a couple, sometimes they 😄 sometimes they 😭

Another point is Mexico has the second largest trading deficit with Colombia. Colombia is a very small trading partner to Mexico. Thus, we see the following figure.

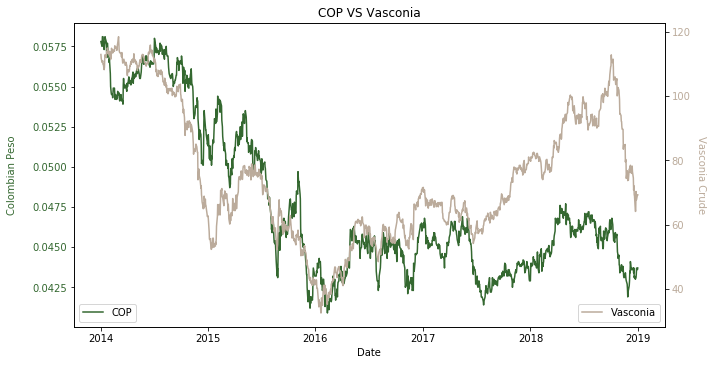

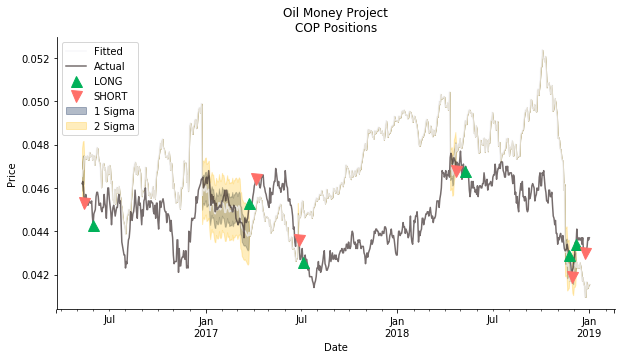

From the chart below, we can observe the intertwined relationship between Colombian Peso and Vasconia Crude until 2017. In 2017, the value of Colombian Peso went fiasco, but the crude oil enjoyed a bonanza caused by OPEC production cut. Intuitively we should split the dataset into two groups, pre-2017 and post-2017.

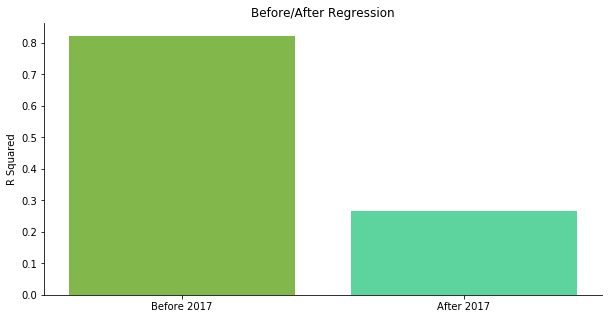

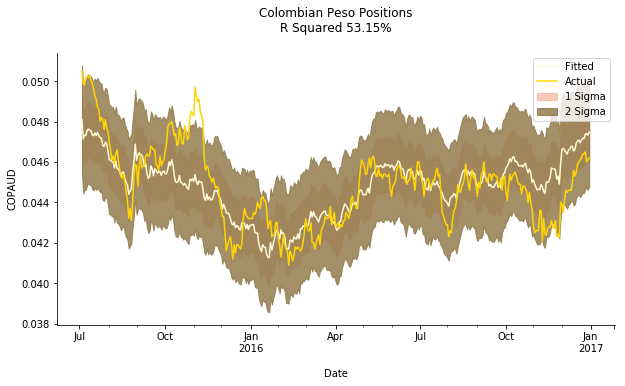

By running a standard oil money regression, pre-2017 dataset demonstrates a bona fide 80% R squared. In comparison, post-2017 dataset confirms no more entangled relationship between Colombian Peso and Vasconia Crude. R squared doesn’t even exceed 30%.

Using a traditional train test split, pre-2017 dataset turns out with a lower R squared, 50%. It seems that all the great fitness comes from late 2015 to 2016. There is only one feasible opportunity on late October of 2015 where the surging momentum could be captured.

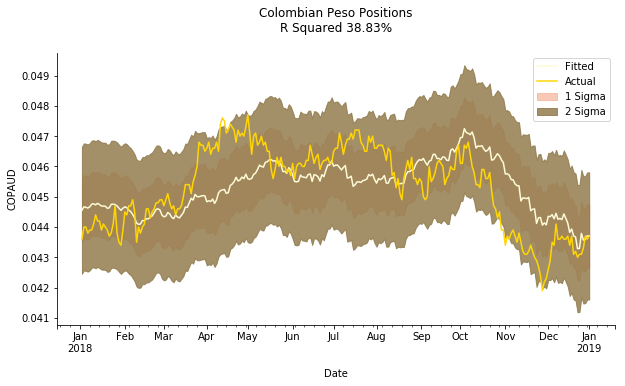

For the post-2017 dataset, things are quite the opposite. The out-of-sample data indicates a higher R squared than in-sample data, about 40%. The whole year of 2018 seems to be a perfect fit where no momentum trading signal emerges. Here comes the greatest dilemma of our strategy. If two assets are perfectly matched, we will lose the chance to make money. Alternatively, if two assets are terribly mismatched or completely detached, we won’t be able to do oil money trading at all. It’s all about the delicate balance of semi-efficient market.

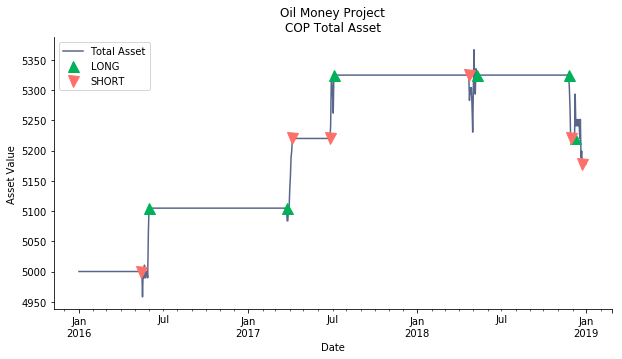

Although we cannot trade Colombian Peso as frequently as Norwegian Krone, the profit of LATAM oil money is as marvelous as Nordic oil money. Judging by the figure below, roughly 70% of the signals generate positive incomes.

Similar to the previous trading tactics, we aim to maximize our profit by searching for the optimal holding period and stop loss/profit. The profit distribution of different parameters is positively skewed. It’s what every investor loves, a positive fat tail. The mean return is respectively 7% (the Colombian interest rate is 4.498% in 2019).

The heatmap tells a consistent story. The return is independent of stop profit/loss point. The length of holding period determines how well we have been riding the waves. The warmer color the tile is, the more profit we will churn out. By setting stop profit/loss point from 0.002 to 0.0045 and holding period at 17 days, we shall be able to achieve our maximum return, 9%! Coincidentally, the excess return α, which interest rate is deducted, for both Norway and Colombia is 4%.

Discussion

In this project, the petrocurrency trading does produce lucrative cash in our account but not the way most market analysts proclaim. Many papers which you will find in further reading session have declared that using oil price to forecast petrocurrency is urban legend. We started off with this awfully wrong direction led by market analysts who are only good at being report 🐒 but suck at conducting quantitative analytics. Fortunately, we ended up on the right foot, discovering a great momentum trading strategy. The greatness of this strategy is its market neutrality. It is reasonably immune to market turmoil or bull run. Moreover, the foundation of this strategy comes from the fundamentals of oil market. Unlike the treasure hunt of tiny anomaly of trading signals, neither the phenomenon will vanish into thin air nor the opportunity will cease to exist when the rest of your competitors catches on to it.

As planned, we have examined three petrocurrencies of free floating FX regime, Norwegian Krone, Russian Ruble, and Colombian Peso. We use solid evidence to debunk the petrocurrency myth of Canadian Dollar. We also strongly advise people to be cautious when dealing with assets from autocratic regimes like Russia. In that sense, we are only left with two options, Norway and Colombia, both alphas are approximately 4%. Well, after such a long time of hard work, perhaps now we deserve an Emirati feast generated by oil wealth.

Further Reading

- Beckmann J, Czudaj R, Arora V (2017) The Relationship Between Oil Prices And Exchange Rates: Theory And Evidence

- Bernhardsen T, Røisland Ø (2000) Factors That Influence The Krone Exchange Rate

- Ferraro D, Rogoff K, Rossi B (2011) Can Oil Prices Forecast Exchange Rates?

- Fratzscher M, Schneider D, Robays IV (2014) Oil Prices, Exchange Rates And Asset Prices

- Ghalayini L (2011) The Interaction Between Oil Price And Economic Growth

- Karlsen JLS, Mjøen MB (2015) Forecasting The Norwegian Krone Exchange Rate Using The Oil Price

This paper was documented by US EIA. It summarized the literatures on short-term and long-term bidirectional forecast, direct and indirect transmission channels, nonlinear relationship, time-variation and related policy implications.

This paper was published by two senior economists of Norges Bank. Who knows Norwegian Krone more than insiders?

This paper was featured by Bank of Canada. Click here for its workshop presentation. Oil Money project uses a similar approach from the paper, yet the results are completely the opposite.

This paper analyzed the causality between oil and asset prices – exploiting the heteroskedasticity of the underlying time-series data. The economists in ECB didn’t only verify the causality between oil price and exchange rate, but also the causality among oil price, equity market shocks and risk shocks.

This paper illustrated the mechanism of how oil shock affects different types of economy. That is why dollar effect matters to our oil money trading.

This paper took two different approaches to construct a true forecasting model. Nonetheless, the random walk seemed to outperform any of these sophisticated models in a high frequency dataset.

Click the icon below to be redirected to GitHub Repository